Previous 1 ... 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 ... 72 Next

I ran across this ^^ while looking at the common ways that we, and as we are discovering other creatures, examine our own thought process.

As we test things, we are finding that other creatures; birds, whales, other primates - are all capable of asking 'what is the best way for me to tackle this problem'. That is, we think about thinking. ![]()

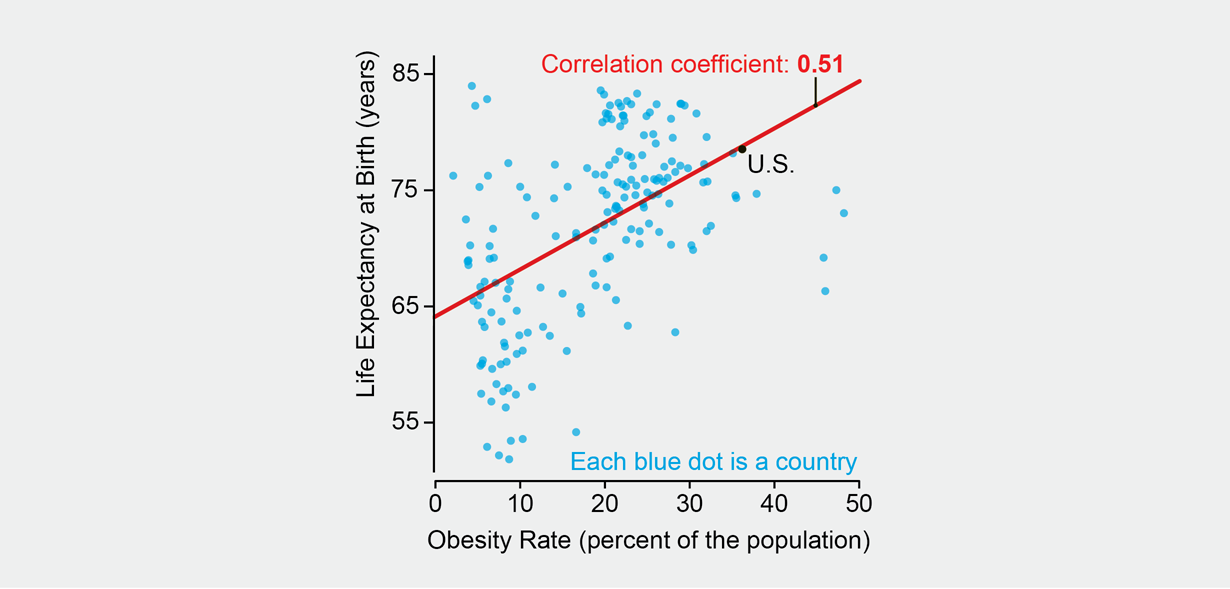

Misreading data visualizations can reinforce biased perceptions

“A picture is worth a thousand words.” That saying leads us to believe that we can readily interpret a chart correctly. But charts are visual arguments, and they are easy to misunderstand if we do not pay close attention. Alberto Cairo, chair of visual journalism at the University of Miami, reveals pitfalls in an example diagrammed here. Learning how to better read graphics can help us navigate a world in which truth may be hidden or twisted.

Say that you are obese, and you’ve grown tired of family, friends and your doctor telling you that obesity may increase your risk for diabetes, heart disease, even cancer—all of which could shorten your life. One day you see this chart (below). Suddenly you feel better because it shows that, in general, the more obese people a country has (right side of chart), the higher the life expectancy (top of chart). Therefore, obese people must live longer, you think. After all, the correlation (red line) is quite strong.

The chart itself is not incorrect. But it doesn’t really show that the more obese people are, the longer they live. A more thorough description would be: “At the national level—country by country—there is a positive association between obesity rates and life expectancy at birth, and vice versa.” Still, this does not mean that a positive association will hold at the local or individual level or that there is a causal link. Two fallacies are involved.

First, a pattern in aggregated data can disappear or even reverse once you explore the numbers at different levels of detail. If the countries are split by income levels, the strong positive correlation becomes much weaker as income rises. In the highest-income nations (chart on bottom right), the association is negative (higher obesity rates mean lower life expectancy).

.png)

. . .

What to Do

Try to see not just what a chart shows but what it may not be showing.

Don’t jump to conclusions, particularly if a chart seems to confirm what you already believe.

Question whether you are correctly verbalizing the chart’s content.

Consider whether the data represent the level required to make the inferences you want. If you want to learn about countries, say, consult data at the country level, but if you want to learn about your own health risks, find data about individuals. And either way, always remember that, in a chart or among any data, correlation is not the same as causation.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/arti ... e-misread/

A deadly outbreak of multi-drug resistant Salmonella that sickened 225 people across the US beginning in 2018 may have been spurred by a sharp rise in the use of certain antibiotics in cows a year earlier, infectious disease investigators reported this week.

From June 2018 to March of 2019, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified an outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype Newport. The strain was resistant to several antibiotics, most notably azithromycin—a recommended treatment for Salmonella enterica infections. Before the outbreak, azithromycin-resistance in this germ was exceedingly rare. In fact, it was only first seen in the US in 2016.

Yet in the 2018-2019 outbreak, it reached at least 225 people in 32 states. Of those sickened, at least 60 were hospitalized and two died. (Researchers didn’t have complete health data on everyone sickened in the outbreak.)

Infectious disease researchers investigating the cases traced the infections back to beef from the US and soft cheeses from Mexico (mostly queso fresco, which is typically made from unpasteurized milk). Genetic testing suggests that cows in both countries are carrying the germ.

. . .

“Avoiding the unnecessary use of antibiotics in cattle, especially those that are important for the treatment of human infections, could help prevent the spread of [multi-drug resistant] Newport with decreased susceptibility to azithromycin.”

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/08 ... e-in-cows/

In my 50s, too old to become a real expert, I have finally fallen in love with algebraic geometry. As the name suggests, this is the study of geometry using algebra. Around 1637, René Descartes laid the groundwork for this subject by taking a plane, mentally drawing a grid on it, as we now do with graph paper, and calling the coordinates x and y. We can write down an equation like x2+ y2 = 1, and there will be a curve consisting of points whose coordinates obey this equation. In this example, we get a circle!

It was a revolutionary idea at the time, because it let us systematically convert questions about geometry into questions about equations, which we can solve if we’re good enough at algebra. Some mathematicians spend their whole lives on this majestic subject. But I never really liked it much until recently—now that I’ve connected it to my interest in quantum physics.

. . .

How could any mathematician not fall in love with algebraic geometry? Here’s why: In its classic form, this subject considers only polynomial equations—equations that describe not just curves, but also higher-dimensional shapes called “varieties.” So, x2+ y2 = 1 is fine, and so is x43 – 2xy2 = y7, but an equation with sines or cosines, or other functions, is out of bounds—unless we can figure out how to convert it into an equation with just polynomials. As a graduate student, this seemed like a terrible limitation. After all, physics problems involve plenty of functions that aren’t polynomials.

. . .

. . .

Had I taken a different path, I might have come to grips with his work through string theory. String theorists postulate that besides the visible dimensions of space and time—three of space and one of time—there are extra dimensions of space curled up too small to see. In some of their theories these extra dimensions form a variety. So, string theorists easily get pulled into sophisticated questions about algebraic geometry. And this, in turn, pulls them toward Grothendieck.

. . .

http://nautil.us/issue/69/patterns/the- ... ntum-world

Our ability to continuously shrink the features of our silicon-based processors appears to be a thing of the past, which has materials scientists considering ways to move beyond silicon. The top candidate is the carbon nanotube, which naturally comes in semiconducting forms, has fantastic electrical properties, and is extremely small. Unfortunately, it has proven extremely hard to grow the nanotubes where they're needed and just as difficult to manipulate them to place them in the right location. There has been some progress in working around these challenges, but the results have typically been shown in rather limited demonstrations.

Now, researchers have used carbon nanotubes to make a general purpose, RISC-V-compliant processor that handles 32-bit instructions and does 16-bit memory addressing. Performance is nothing to write home about, but the processor successfully executed a variation of the traditional programming demo, "Hello world!" It's an impressive bit of work, but not all of the researchers' solutions are likely to lead to high-performance processors.

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/08 ... nanutubes/

And the Study:

Electronics is approaching a major paradigm shift because silicon transistor scaling no longer yields historical energy-efficiency benefits, spurring research towards beyond-silicon nanotechnologies. In particular, carbon nanotube field-effect transistor (CNFET)-based digital circuits promise substantial energy-efficiency benefits, but the inability to perfectly control intrinsic nanoscale defects and variability in carbon nanotubes has precluded the realization of very-large-scale integrated systems. Here we overcome these challenges to demonstrate a beyond-silicon microprocessor built entirely from CNFETs. This 16-bit microprocessor is based on the RISC-V instruction set, runs standard 32-bit instructions on 16-bit data and addresses, comprises more than 14,000 complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor CNFETs and is designed and fabricated using industry-standard design flows and processes. We propose a manufacturing methodology for carbon nanotubes, a set of combined processing and design techniques for overcoming nanoscale imperfections at macroscopic scales across full wafer substrates. This work experimentally validates a promising path towards practical beyond-silicon electronic systems.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1493-8

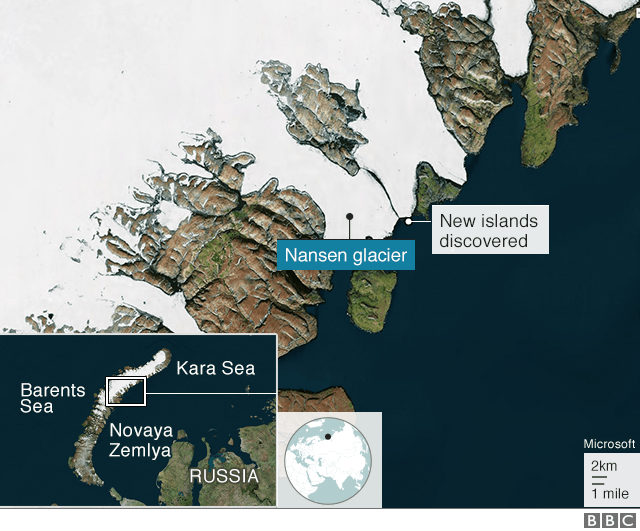

A Russian Arctic expedition has mapped five small islands in the far north, discovered by a student analysing a glacier's retreat in satellite photos.

Before Marina Migunova's discovery in 2016 the islands were hidden under the Nansen Glacier, also known as Vylka, in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago.

Her discovery was part of her final coursework at the Admiral Makarov State Maritime Academy in St Petersburg.

Maps are being updated as global warming melts ice across the Arctic.

. . .

Also known by the Russian initials GUMRF, the academy says its specialists found more than 30 new islands, capes and bays there in 2015-2018.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-49510721

I thought that global warming would make islands disappear, not appear. ![]()

![]()

![]() Melting ice makes for less mass on land, and the land sometimes rises because of it.

Melting ice makes for less mass on land, and the land sometimes rises because of it.

It's seen quite vividly in Greenland and Alaska, where they've lost a lot of mass due to melting.

For 6,000 years, humans have been making things from metal because it's strong and tough; a lot of energy is required to damage it. The flip side of this property is that a lot of energy is required to repair that damage. Typically, the repair process involves melting the metal with welding torches that can reach 6,300 °F.

Now, for the first time, Penn Engineers have developed a way to repair metal at room temperature. They call their technique "healing" because of its similarity to the way bones heal, recruiting raw material and energy from an external source.

The study was conducted by James Pikul, assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics and Zakaria Hsain, a graduate student in his lab.

It was published in the journal Advanced Functional Materials.

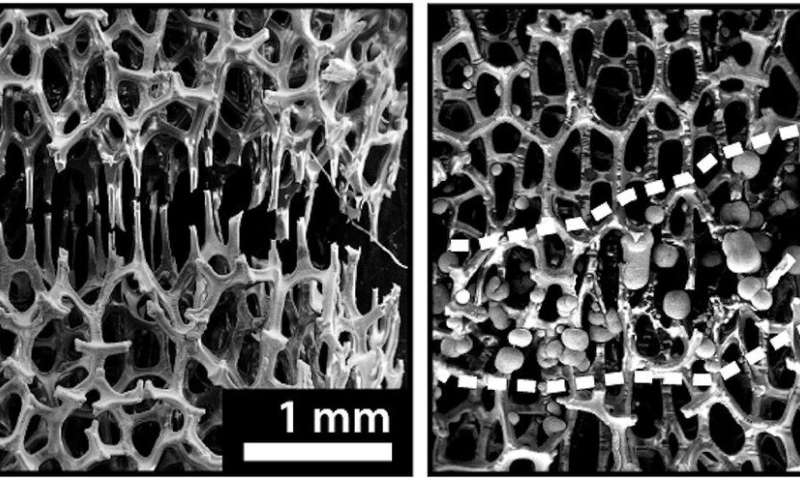

Beyond the energy costs associated with the current process of repairing metal by melting it to a more pliable form, there are some metal components where such a repair strategy is not even an option. For example, melting removes the intricate internal structure of metallic foams, which are metals made with internal pockets of air. This arrangement of struts and gaps reduces the material's weight while maintaining its overall strength.

https://phys.org/news/2019-08-bone-like ... ature.html

What makes a good construction material? There are many requirements, but one is the ability to efficiently connect different parts. Steel is almost the perfect example: you can join steel with fasteners (like nuts and bolts), by brazing, or by welding. The last of these is especially important. If we couldn’t weld metals, life would be quite different.

You don't see this with ceramics. Ceramic parts are the hard-wearing miracle of modern life, but unlike steel and aluminum, you won’t find ceramics everywhere. This is because ceramics, though very useful, are difficult to work with. Joining two ceramics, or even connecting a ceramic to a metal, is a difficult and energy-consuming process because ceramics cannot be welded. That has changed, thanks to a team of researchers who are developing a ceramic welding laser.

Welding is riveting

Welding is a really special process. At one level, it is very simple: heat two materials until they melt and flow together. However, the melting is only local, so that there is only minimal deformation to the rest of the part. The joint needs to be strong, which means that changes to the structure of the metal should not be too dramatic. Melting metals tend to oxidize vigorously, complicating the process.

Ceramic welding should be similar. The ceramic parts would be heated locally so that they melt and pool together. On cooling, the liquid recrystallizes to recreate the ceramic. Since ceramics are oxidized already, you don’t even have to worry too much about setting yourself on fire—a relief to me, as I have a bit of a flaming track record.

The problem is delivering heat to the right location. Since ceramics don’t conduct much heat, lasers are the weapon of choice for precision heating. Unfortunately, ceramics don’t efficiently absorb light; instead, they're actually really good at scattering light. That means that the laser does not form a nice focus at the weld location and ends up gently heating a wide area of ceramic.

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/08 ... ed-joints/

If you’ve spent much time thinking about the political divide in the United States, you’ve hopefully noted how bloody weird it is. Somehow, just about every topic that people want to argue about splits into two camps. If you visualize the vast array of topics you could have an opinion about as a switchboard full of toggles, it seems improbable that so many people in each camp should have nearly identical switchboards, but they do. This can even extend to factual issues, like science—one camp typically does not accept that climate change is real and human-caused.

How in the world do we end up with these opinion sets? And why does something like climate change start an inter-camp argument, while other things like the physics behind airplane design enjoy universal acceptance?

One obvious way to explain these opinions is to look for underlying principles that connect them. Maybe it’s ideologically consistent to oppose both tax increases and extensive government oversight of pesticide products. But can you really draw a straight line from small-government philosophy to immigration attitudes? Or military funding?

Politics and hit songs

A new study by a Cornell team led by Michael Macy approaches these questions with inspiration from an experiment involving, of all things, downloading indie music. That study set up separate “worlds” in which participants checked out new music with the aid of information about which songs other people in their experimental world were choosing. It showed that the songs that were “hits” weren’t always the same—there was a significant role for chance, as a song that got trending early in the experiment had a leg up.

To see if this sort of “accident of history” model could apply to political divisions, the researchers set up a similar experiment. A total of over 4,500 online participants were split into two experiments where each had an equal number of self-identified Democrats and Republicans. The researchers then created ten separate “worlds” in each experiment.

. . .

This fairly subtle change (along with the promise of a $100 prize for the top predictor) apparently got people’s brains working differently. In this version of the experiment, social influence was a little less important, and a significant number of people voted contrary to the trend. The final results turned out more similar to the outcome of the two worlds in which there was no social information provided. Still, the early responses in the social worlds was still the best predictor of how each one would end up.

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/09 ... pressured/

tl;dr: Politics is just an artificial construct, easily circumvented.

Physicists at York University in Toronto have spent the last eight years meticulously conducting a sensitive experiment to measure the charge radius of the proton in hopes of resolving conflicting values obtained by several similar experiments performed over the last decade. That conundrum has been dubbed the "proton radius puzzle." The new results, published in a new paper in Science, confirm a 2010 finding that the proton is significantly smaller than scientists previously believed.

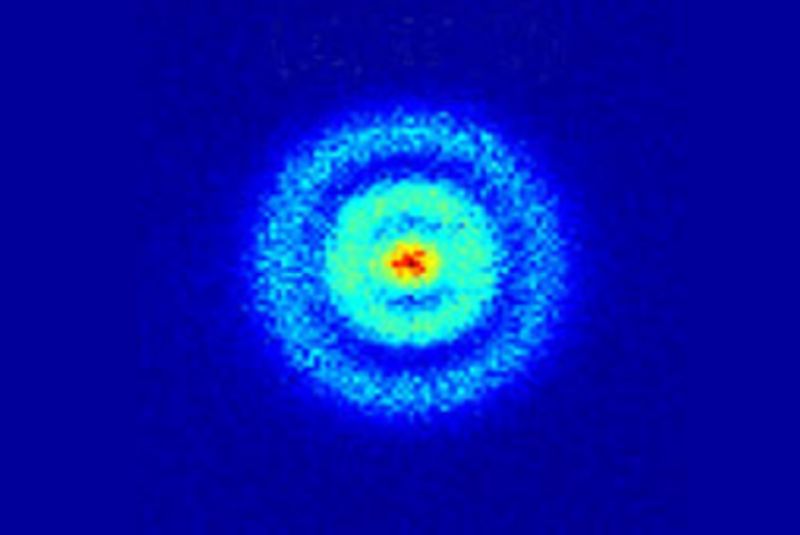

Most popularizations discussing the structure of the atom rely on the much-maligned Bohr model, in which electrons move around the nucleus in circular orbits. It's fine as a gateway drug to physics, so to speak, but quantum mechanics gives us a much more precise (albeit weirder) description. The electrons aren't really orbiting the nucleus; they are technically waves that take on particle-like properties when we do an experiment to determine their position. While orbiting an atom, they exist in a superposition of states, both particle and wave, with a wave function encompassing all the probabilities of its position at once. A measurement will collapse the wave function, giving us the electron's position. Make a series of such measurements and plot the various positions that result, and it will yield something akin to a fuzzy orbit-like pattern.

Quantum weirdness extends to the proton, too. Technically it's made of three charged quarks bound together by the strong nuclear force. But it's fuzzy, like a cloud. And how can we talk about the radius of a cloud? Physicists rely on the charge density to do so, akin to the density of water molecules in a cloud. The radius of the proton is the distance at which the charge density drops below a certain energy threshold. And it's possible to measure that radius by studying how the electron interacts with the proton, via either electron scattering experiments or by using electron or muon spectroscopy to look at the difference between atomic energy levels. (It's called the "Lamb shift," after Nobel laureate Wallis Lamb, who first measured the shift in 1947.) The combined fuzziness of the electron and proton means that the electron can be anywhere inside that region—including inside the proton.

Hydrogen atoms are the simplest nuclei, with a single proton orbited by an electron, so that's typically what physicists have used for their experiments to measure the proton's charge radius. For a long time, the accepted value was .876 femtometers—a "world average" of many different measurements with sufficient error bars to allow for future measurements.

. . .

The result: their measurement of 0.833 femtometers (just under one-trillionth of a meter) agrees with the smaller value from the 2010 study. That's good news for the Standard Model and bad news for those hoping for some exciting new physics. "Because it's a direct comparison, it certainly makes a pretty strong case for the smaller size being the correct size," said Hessels. Additional experiments by other groups are currently underway, and he expects the community will converge on a consensus as those results trickle in over the next couple of years.

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/09 ... us-puzzle/

The Doomed Mouse Utopia That Inspired the ‘Rats of NIMH’

This is a far cry from a wild mouse’s life—no cats, no traps, no long winters. It’s even better than your average lab mouse’s, which is constantly interrupted by white-coated humans with scalpels or syringes. The residents of Universe 25 were mostly left alone, save for one man who would peer at them from above, and his team of similarly interested assistants. They must have thought they were the luckiest mice in the world. They couldn’t have known the truth: that within a few years, they and their descendants would all be dead.

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the- ... ket-newtab

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/45/40/4540b5c1-a6c5-430c-bf10-e9fcbc48bbdc/dishes_and_bottles.jpg)

In 2004, archaeology professor Robert Muckle was alerted to a site within the forests of British Columbia’s North Shore mountains, where a few old cans and a sawblade had been discovered. He suspected the area was once home to a historic logging camp, but he did not anticipate that he would spend the next 14 years unearthing sign after sign of a forgotten Japanese settlement—one that appears to have been abruptly abandoned.

Brent Richter of the North Shore News reports that Muckle, an instructor at Capilano University in Vancouver, and his rotating teams of archaeology students have since excavated more than 1,000 items from the site. The artifacts include rice bowls, sake bottles, teapots, pocket watches, buttons and hundreds of fragments of Japanese ceramics. Muckle tells Smithsonian that the “locations of 14 small houses … a garden, a wood-lined water reservoir, and what may have been a shrine,” were also discovered, along with the remnants of a bathhouse—an important fixture of Japanese culture.

The settlement sits within an area now known as the Lower Seymour Conservation Reserve, located around 12 miles northeast of Vancouver. Muckle has in fact uncovered two other sites within the region that can be linked to Japanese inhabitants: one appears to have been part of a “multi-ethnic” logging camp, Muckle says, the second a distinctly Japanese logging camp that was occupied for several years around 1920. But it is the third site, which seems to have transitioned from a logging camp to a thriving village, that fascinates him the most.

“There was very likely a small community of Japanese who were living here on the margins of an urban area,” Muckle tells Richter. “I think they were living here kind of in secret.”

In approximately 1918, a Japanese businessman named Eikichi Kagetsu secured logging rights to a patch of land next to where the village once stood, making it likely that the site was once inhabited by a logging community. The trees would have been largely harvested by around 1924, but Muckle thinks the village’s residents continued to live there past that date.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-ne ... 180973028/

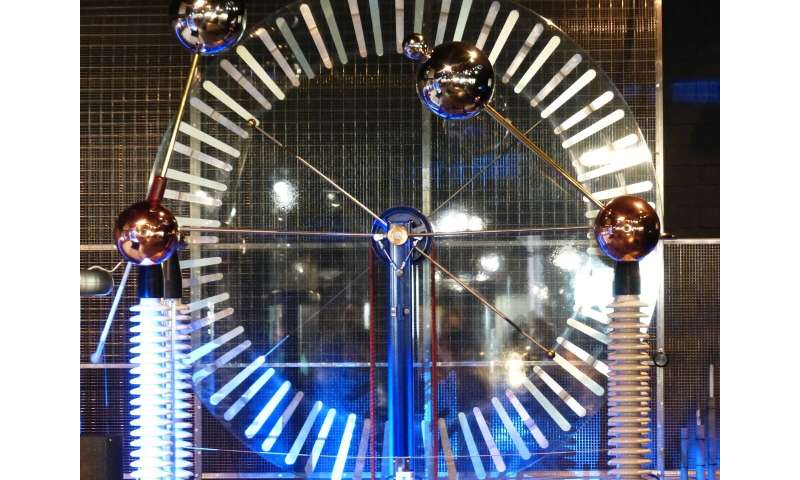

Most people have experienced the hair-raising effect of rubbing a balloon on their head or the subtle spark caused by dragging socked feet across the carpet. Although these experiences are common, a detailed understanding of how they occur has eluded scientists for more than 2,500 years.

Now a Northwestern University team developed a new model that shows that rubbing two objects together produces static electricity, or triboelectricity, by bending the tiny protrusions on the surface of materials.

This new understanding could have important implications for existing electrostatic applications, such as energy harvesting and printing, as well as for avoiding potential dangers, such as fires started by sparks from static electricity.

The research will be published on Thursday, Sept. 12, in the journal Physical Review Letters. Laurence Marks, professor of materials science and engineering in Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering, led the study. Christopher Mizzi and Alex Lin, doctoral students in Marks's laboratory, were co-first authors of the paper.

. . .

"This is a great example of how fundamental research can explain everyday phenomena which hadn't been understood previously, and of how research in one area—in this case friction and wear—can lead to unexpected advances in another area," said Andrew Wells, a program director at the National Science Foundation (NSF), which funded the research. "NSF funds research like this in materials science and engineering for new knowledge that can one day open new opportunities."

https://phys.org/news/2019-09-longstand ... icity.html

Previous 1 ... 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 ... 72 Next