Previous 1 ... 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 ... 75 Next

Why didn't they just say that this is slime mold... Physarum polycephalum being it's real name.

I'm not sure about the unicellular thing though since you can't really see one cell with the naked eye but a colony can be seen.

Interesting stuff about this mold...

It has been claimed that because plasmodia appear to react in a consistent way to stimuli, they are the "ideal substrate for future and emerging bio-computing devices".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Physarum_polycephalum

There's a little extra thumb-thing on the hand of the aye-aye, a strange-looking nocturnal lemur native to Madagascar. Tucked near each wrist is a small nub of bone and cartilage that's like a miniature thumb — and until recently, scientists didn't know this pseudothumb existed.

Aye-ayes (Daubentonia madagascariensis) are considered by many to be the weirdest of all primates, with their coarse and frazzled bedhead fur, oversize ears, bulging eyes and bony, spindly fingers, one of which is exceptionally long.

But the discovery of the hidden mini-thumb makes aye-ayes even weirder: They are the only primate to have evolved an extra finger to help with grasping. The formerly unknown digit even has its own fingerprint, scientists reported in a new study.

n local Malagasy folklore, aye-ayes are seen as symbols of death and evil, capable of delivering curses and bringing bad luck, according to the Duke Lemur Center in North Carolina.

However, the aye-ayes' long, flexible fingers are best suited not for cursing humans, but for tapping on tree branches to locate hollow regions where tasty grubs hide, and then to poke inside holes and fish insects out, the Duke Lemur Center said.

"Their fingers have evolved to be extremely specialized — so specialized, in fact, that they aren't much help when it comes to moving through trees," said co-lead study author Adam Hartstone-Rose, an associate professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University (NCSU).

Aye-aye hands are so strange that when the animals move they appear to be "walking on spiders," Hartstone-Rose said in a statement. It could be this extreme adaptation that drove the evolution of an extra digit to help with grasping, which aye-ayes' long, skinny fingers couldn't manage very well, the researchers wrote in the study.

https://www.livescience.com/aye-aye-second-thumb.html

New Scientist reported the strange case of a 46-year-old man in the U.S. whose body started brewing beer in his gut after it accidentally became home to high levels of brewer’s yeast. He began suffering many of the symptoms of being drunk such as mental fogginess and memory loss and had to quit his job.

He saw several doctors, none of which could find what was wrong. This is not the first such case. In fact, the condition has a name: auto brewery syndrome.

Back in 2013, a Texas man suffered from the same condition. The 61-year-old man stumbled in a hospital and was found to have a blood alcohol level of .37.

However, he insisted he hadn’t had a single drop of alcohol all day. In a report published in Scientific Research Publishing, U.S. researchers Barbara Cordell and Dr. Justin McCarthy tested out what they call “gut fermentation syndrome.”

Soon enough they found that the patient had an infection with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a common yeast. When he consumed starch the yeast fermented along with the sugars, turning into ethanol. He was essentially brewing beer in his gut.

https://interestingengineering.com/a-ma ... in-his-gut

Tell me more about your "infinite beer" pills.

A copper oxide mineral's crystals look out of this world at high magnification.

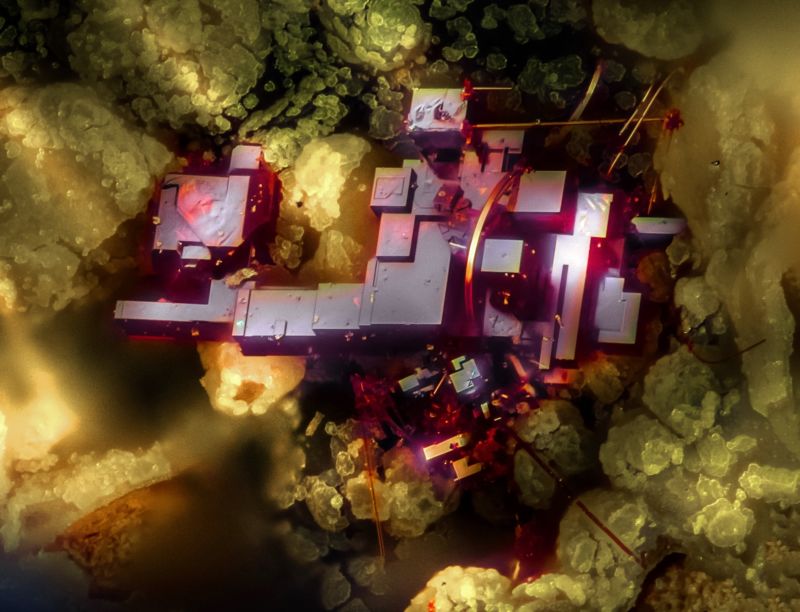

This alien-looking landscape is formed by mold; the "trees" are how it makes and spreads its spores.

This is a lynx spider, which has some flamboyant coloration around its eight eyes.

No, that's not a punk haircut. Those are fine sensory bristles on the antennae of a male mosquito. In other species, similar hairs are used to pick up female pheromones.

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/10 ... l-winners/

A programmable quantum computer has been reported to outperform the most powerful conventional computers in a specific task — a milestone in computing comparable in importance to the Wright brothers’ first flights.

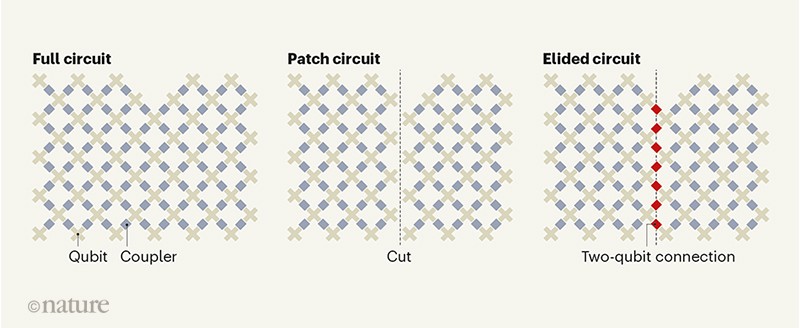

Quantum computers promise to perform certain tasks much faster than ordinary (classical) computers. In essence, a quantum computer carefully orchestrates quantum effects (superposition, entanglement and interference) to explore a huge computational space and ultimately converge on a solution, or solutions, to a problem. If the numbers of quantum bits (qubits) and operations reach even modest levels, carrying out the same task on a state-of-the-art supercomputer becomes intractable on any reasonable timescale — a regime termed quantum computational supremacy1. However, reaching this regime requires a robust quantum processor, because each additional imperfect operation incessantly chips away at overall performance. It has therefore been questioned whether a sufficiently large quantum computer could ever be controlled in practice. But now, in a paper in Nature, Arute et al.2 report quantum supremacy using a 53-qubit processor.

Read the paper: Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor

Arute and colleagues chose a task that is related to random-number generation: namely, sampling the output of a pseudo-random quantum circuit. This task is implemented by a sequence of operational cycles, each of which applies operations called gates to every qubit in an n-qubit processor. These operations include randomly selected single-qubit gates and prescribed two-qubit gates. The output is then determined by measuring each qubit.

The resulting strings of 0s and 1s are not uniformly distributed over all 2n possibilities. Instead, they have a preferential, circuit-dependent structure — with certain strings being much more likely than others because of quantum entanglement and quantum interference. Repeating the experiment and sampling a sufficiently large number of these solutions results in a distribution of likely outcomes. Simulating this probability distribution on a classical computer using even today’s leading algorithms becomes exponentially more challenging as the number of qubits and operational cycles is increased.

In their experiment, Arute et al. used a quantum processor dubbed Sycamore. This processor comprises 53 individually controllable qubits, 86 couplers (links between qubits) that are used to turn nearest-neighbour two-qubit interactions on or off, and a scheme to measure all of the qubits simultaneously. In addition, the authors used 277 digital-to-analog converter devices to control the processor.

. . .

When 53 qubits were operating over 20 cycles, the XEB fidelity calculated using these proxies remained greater than 0.1%. Sycamore sampled the solutions in a mere 200 seconds, whereas classical sampling at 0.1% fidelity would take 10,000 years, and full verification would take several million years.

. . .

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03173-4

In my previous installment of this column, I wrote about a fundamental difference between mathematics and physics: The former is a deductive endeavor in which the conclusions follow with certainty from the premises, and the latter is grounded in observations, measurements, and inductive reasoning.

You could imagine a world where that distinction didn’t exist—where math was just as much an experimental science as physics is. To find the formula for the area of a circle, for example, geometers (“Earth measurers”) would draw a lot of circles, estimate their areas, and look for a pattern. It would never occur to anyone that the pattern should be verified with a proof; the observations would speak for themselves.

That we don’t live in that world has a lot to do with the work of Euclid of Alexandria. Euclid probably didn’t invent the idea of a mathematical proof, but he sure helped it catch on: His magnum opus, the Elements, written around 300 BCE, is arguably the most influential textbook of all time. For more than 2000 years, students learned geometry exactly the way Euclid taught it—as a series of theorems deduced from a modest set of five postulates and five “common notions.”

By today’s standards of mathematical rigor, Euclid leaves a lot to be desired. His proofs are full of implicit assumptions—for example, that for any two points on a line, there are more points between them—that he should have included in his list of postulates but didn’t. To his great credit, though, he did recognize the need to include his infamous parallel postulate.

As learned by today’s geometry students, the parallel postulate states that for any line ℓ and any point P not on ℓ, there is exactly one line through P that’s parallel to ℓ. Euclid’s original version was a bit clunkier, but the statements are logically equivalent.

The parallel postulate bothered a lot of people for a long time. (Those people probably included Euclid himself—tellingly, he put off invoking it in the Elements for as long as he could.) The problem, I suspect, is that it’s just the right mix of obvious and nonobvious, and it can never be empirically confirmed. The Euclidean plane is infinitely large, and some of the lines through P intersect ℓ an incomprehensible distance away. To convince yourself that one and only one of them never intersects ℓ at all, you need to make a conceptual leap from the part of the plane you can visualize to the part that you can’t. And yet, it seemed like the postulate just had to be true; for 2000 years, no one was willing to seriously entertain the possibility that it wasn’t.

If it had to be true but wasn’t self-evident enough to assume, then could it perhaps be a theorem that followed from the other postulates? A proof would settle the matter, and for 2000 years mathematicians tried to find one. They weren’t lightweights, either—some of the brightest mathematical minds of the ages were positively obsessed with proving the parallel postulate. They all failed. Every one of their proofs contained some unjustified assumption.

On the bright side, those assumptions make up a convenient list of statements that are logically equivalent to the parallel postulate. Many of them are familiar to the geometry students of today, such as: Parallel lines are everywhere equidistant.

Or: The angles of a triangle add up to 180°.

Or: Rectangles exist.

Now, if you haven’t heard this story before, you might think it’s getting a bit ridiculous. Isn’t it obvious that rectangles exist? They’re everywhere, after all. Unlike lines that may or may not intersect millions of miles away, rectangles can be drawn, and seen, and studied, right under our noses. Any material rectangle is at best an approximation of the Platonic ideal rectangle—a figure with four perfectly right angles—but surely that’s just because humans are imperfect at drawing rectangles, not because the Platonic form doesn’t exist, right?

If you have heard this story before, then you know what happens next: Over the course of the 19th century, it came to light that the parallel postulate—and the existence of rectangles—could never be proved because there are alternative geometries, just as self-consistent as Euclidean geometry, in which it’s false. There’s hyperbolic geometry, in which there are infinitely many lines (or as mathematicians sometimes put it, “at least two”) through P that are parallel to ℓ. And there’s elliptic geometry, which contains no parallel lines at all.

. . .

So far, it looks like the cosmos is as close to flat as can be measured. But the nature of continuous measurements is that they’re always inexact, and the nature of Euclidean geometry is that it postulates an exactness—there’s exactly one line through P parallel to ℓ, the angles of a triangle add up to exactly 180°—that’s beyond what can ever be observed. Maybe someday cosmological measurements will be good enough to reveal that the universe isn’t Euclidean, but they’ll never be able to conclusively show that it is.

The parallel postulate and the existence of rectangles, which seemed so obvious to so many for so long, will remain forever unverified.

https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/1 ... 018a/full/

I love this stuff... ![]()

...isn't a rectangle just 2 or more triangles? ![]()

...isn't a rectangle just 2 or more triangles?

Not equilateral triangles though.

I love this stuff too.

You can have as many equilateral triangles as you want, but you have to finish off 2 sides with another kind of triangle. In this case, 2 right triangles. But you could add 2 more equilateral triangles to each side and finish with 2 isosceles triangles.

See, you've got yourself an Isocelese Zoid trap there.

Triangles are heavily used in games to produce textures because they are quick to calculate, and can approximate most other shapes.

...isn't a rectangle just 2 or more triangles?

Not equilateral triangles though.

I love this stuff too.

Cladistic dude, cladistics

As nasty as the asteroid impact at the end of the Cretaceous sounds, you wouldn't think scientists would be spending much time asking, "Yeah, but how did things actually die?"

It's not just a macabre fascination. With so many awful things going on at once—including a remarkable stretch of volcanic eruptions in what is now India—there are a handful of kill mechanisms to choose from. And when you closely examine the patterns of which species in which environments went extinct, the picture gets complicated.

One major question has been the extinctions in the oceans. On land, there were several years of freezing temperatures and sunless skies, not to mention the tsunamis and worldwide wildfires. The oceans have a tremendous thermal mass, however, that would have moderated the global chill. In the deep ocean, the loss of sunlight wouldn't be felt as immediately.

Further Reading

End-Cretaceous asteroid impact seems to have juiced seafloor volcanoes

After the skies cleared, potent global warming set in for the long haul due to the CO2 produced when the impactor evaporated bedrock to make the impact crater. The ongoing volcanic eruptions in India were also emitting CO2, and there's even evidence that seafloor volcanism picked up due to the impact.

Dropping (due to) acid

Just like today, that increase in atmospheric CO2 would be associated with acidification of the oceans. That's what a team of researchers led by Michael Henehan at GFZ Potsdam focused on in a new study.

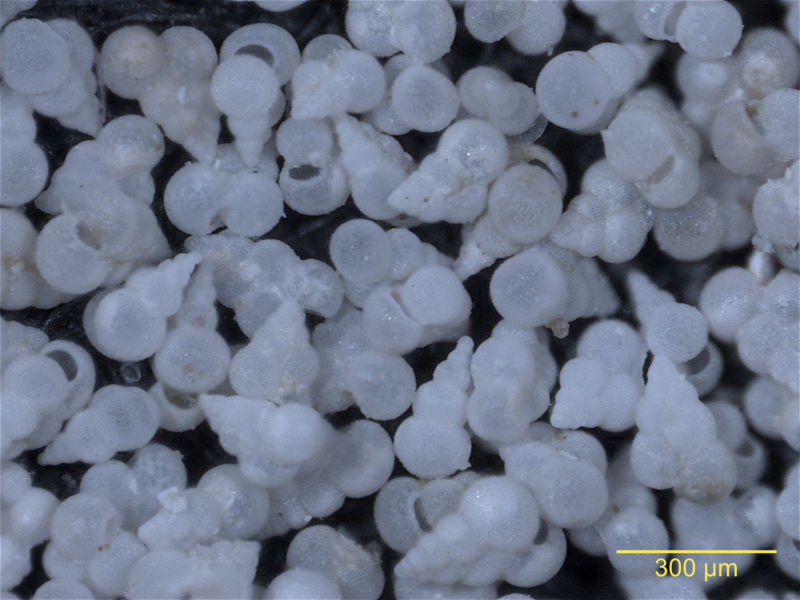

From a handful of seafloor sediment cores, the team measured isotopes of boron in the tiny calcium carbonate shells of single-celled organisms called forams. Some forams are plankton, floating near the surface, while others live on the seafloor—meaning they can show you what was happening in both environments. And the boron isotopes they incorporate into their shells will shift along with the pH of seawater.

The first thing to look at is actually what was happening before the asteroid impact. Despite the intense volcanic eruptions in that period, ocean pH seems to have been steady for quite some time. But right after the impact event, that changes.

The reconstructed surface ocean pH shows a sharp drop from 7.8 to about 7.5. As the pH scale is logarithmic, that's a huge swing. For context, our CO2 emissions since the Industrial Revolution have, so far, decreased ocean pH from about 8.2 to about 8.1—a 30% increase in acidity.

A pH change of that scale would signify an increase of atmospheric CO2 from about 900 parts per million to 1,600 parts per million. (For context, again, today's concentration is about 410 parts per million. The Cretaceous was a warm period in Earth's climate history.)

https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/10 ... -ocean-ph/

A study linking fluoride exposure in pregnancy to lower IQ scores in boys is unnecessarily frightening people into avoiding fluoridated water, researchers say

When the editor-in-chief of a highly reputable American medical journal decided to publish a potential bombshell study from Canada hinting that pregnant women who drink fluoridated water risk subtly damaging their child’s brain, he braced for the blowback.

He worried anti-fluoridationists would sink their teeth into it and wave it as the definitive study, and that proponents of fluoride would trash it “because they just don’t want to believe the findings,” Dr. Dimitri Christakis, editor of JAMA Pediatrics said in an interview with the Post.

Well, he certainly called it.

Anti-fluoride activists are demanding a moratorium on fluoridation and an end to a “human experiment on millions of children,” while an international group of academics has now taken the rare step of urging the study’s American funder to formally request that the authors of the controversial paper release their data for independent review.

“So much is at stake,” reads the group’s appeal sent this week to the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The former chief dental officer for England, the chair of the Royal Society for Public Health in the U.K. and Timothy Caulfield, Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy at the University of Alberta, are among the 30 signatories.

“Hundreds of millions of people around the globe — from Brazil to Australia — live in homes that receive fluoridated drinking water,” the letter states. “Hundreds of millions of people use toothpaste or other products with fluoride. Many millions of children receive topical fluoride treatments.”

The authors argue, among other concerns, that the York University-led paper that suggested children born to women exposed to higher levels of fluoride during pregnancy have lower IQs is riddled with inconsistencies and “incongruities,” that it focused a significant portion of its narrative on boys, that it didn’t take the mother’s IQ scores into account, and that it used invalid measures to determine just how much fluoride the mothers were exposed to.

They’re also displeased with the way it was presented to the public, saying it has caused confusion and scary headlines that could influence public policy. (The study’s senior author, York psychology professor Christine Till, told Time magazine that instructing pregnant women to reduce their fluoride intake is a “no brainer.”)

The fallout from the article is particularly harmful in Calgary, the academics said, where it’s being cited as reason not to resume water fluoridation eight years after the city ceased adding fluoride to tap water. (Calgary city council is holding a public hearing on fluoridation Tuesday evening).

https://nationalpost.com/health/so-much ... ride-study

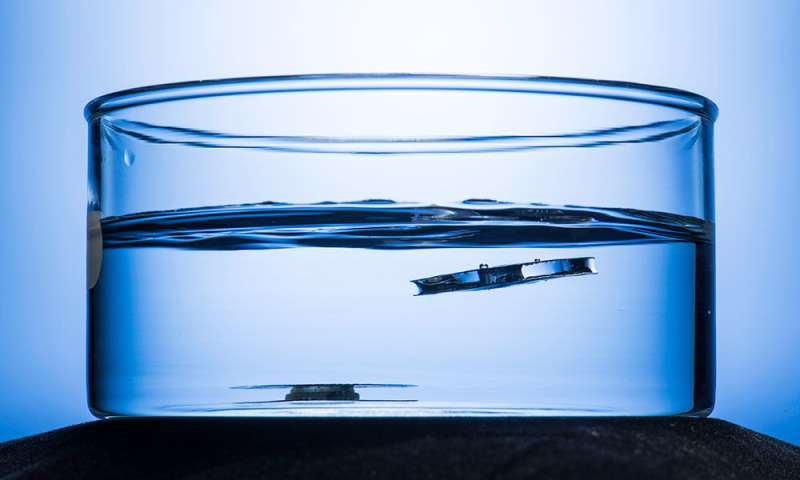

University of Rochester researchers, inspired by diving bell spiders and rafts of fire ants, have created a metallic structure that is so water repellent, it refuses to sink—no matter how often it is forced into water or how much it is damaged or punctured.

Could this lead to an unsinkable ship? A wearable flotation device that will still float after being punctured? Electronic monitoring devices that can survive in long term in the ocean?

All of the above, says Chunlei Guo, professor of optics and physics, whose lab describes the structure in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.

The structure uses a groundbreaking technique the lab developed for using femtosecond bursts of lasers to "etch" the surfaces of metals with intricate micro- and nanoscale patterns that trap air and make the surfaces superhydrophobic, or water repellent.

https://phys.org/news/2019-11-spiders-a ... -wont.html

In modern cities, we're constantly surveilled through CCTV cameras in both public and private spaces, and by companies trying to sell us shit based on everything we do. We are always being watched.

But what if a simple T-shirt could make you invisible to commercial AIs trying to spot humans?

A team of researchers from Northeastern University, IBM, and MIT developed a T-shirt design that hides the wearer from image recognition systems by confusing the algorithms trying to spot people into thinking they're invisible.

Adversarial designs, as this kind of anti-AI tech is known, are meant to "trick" object detection algorithms into seeing something different from what's there, or not seeing anything at all. In some cases, these designs are made by tweaking parts of a whole image just enough so that the AI can't read it correctly. The change might be imperceptible to a human, but to a machine vision algorithm it can be very effective: In 2017, researchers fooled computers into thinking a turtle was a rifle.

https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/evj9 ... ible-to-ai

Previous 1 ... 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 ... 75 Next